Asian Art in London 2025: The Shangri Ramayana

For Asian Art in London 2025 , Rob Dean Art presents an online exhibition of ten folios from the Shangri Ramayana.

The present group of paintings, collectively known as the Shangri Ramayana, constitutes one of the most enigmatic and scholastically complex bodies of work from the Pahari region. No scholarly consensus exists regarding its precise dating, provenance, patronage, or stylistic affiliation. Based on the narrative of Valmiki’s Ramayana, the set is arguably the most ambitious and monumental in scale among extant Pahari series. A substantial portion of the paintings is presently housed in the National Museum, New Delhi, while the remaining works are dispersed in collections across the world. The bulk of the series is known to have once belonged to Raja Raghubir Singh of Kulu, from the ‘Shangri’ branch of the ruling house—hence the appellation by which it is now recognised.

The paintings first received sustained scholarly attention in the pioneering work of W. G. Archer. Since Archer’s analysis was primarily grounded in stylistic evaluation, his examination led to the division of the set into four stylistic categories—Style I, Style II, Style III, and Style IV—a classification that remains relevant to scholarly debate today. While acknowledging that the paintings were executed by different hands and at different times, Archer maintained that the set was produced for the Kulu court, whose rulers were deeply devoted to Rama. This devotion was exemplified by the fact that one of the kings is recorded to have abdicated his throne to become a monk in Ayodhya, the legendary capital of Rama.

Subsequent and more recent scholarship, particularly the analysis by B.N. Goswamy and Eberhard Fischer, has offered an alternative interpretation. They propose that the set can be bifurcated into two distinct parts: Styles I, II, and III are attributed to Bahu, a centre within the erstwhile Jammu state. Within this grouping, the twenty-four paintings rendered in Style I are ascribed to the so-called “First Bahu Master,” whose stylistic and compositional innovations demonstrably influenced the works in Styles II and III, dated to the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Style IV, by contrast, differs markedly from the earlier styles, appearing to have been produced by painters operating with a greater degree of autonomy, independent of the directives that shaped Styles I–III.

Part of the enigma surrounding the Shangri Ramayana lies in the divergences not only in style and typology, but also in the inscriptions that accompany the works. In Style I, inscriptions typically identify the Ramayana chapter depicted, whereas in Style III, the margins bear extensive vernacular Pahari inscriptions narrating the episode in detail on all four sides of the composition. Recent scholarship has posited the possibility that the paintings may have been produced in different centres, at different times, for different patrons, and only later, by coincidence, assembled into a single collection. This theory, however, encounters the difficulty that no episode appears twice in two different hands, and that the various painters seem to have been cognisant of each other’s contributions. Such evidence implies at least some degree of coordination or shared knowledge among the participating artists. However, additional folios from the dispersed series have come to light since Archer’s original ground-breaking analysis and these raise further questions concerning style and artistic attribution. Although Archer’s Styles I – IV remain a useful framework for art historical debate it is clear that many distinct hands can be distinguished across the series that divides these styles into smaller subdivisions of work, that again supports a theory of multiple smaller ateliers working on different sections of the story, but possibly under one or two co-ordinated centres of overall manufacture.

The Shangri Ramayana remains compelling not only for its unresolved questions of origin, and the number of artists involved in its creation, but also for the dramatic force of its imagery. Particularly striking are the later episodes—Kishkindha Kanda, Sundara Kanda, and Lanka Kanda—traditionally associated with Styles III and IV, which are visually dynamic and charged with narrative tension. These sections, comprising Rama’s arduous campaign against Ravana’s formidable forces, stand in deliberate contrast to the courtly grandeur of the Bala Kanda and Ayodhya Kanda, and the contemplative forest scenes of the Aranya Kanda. The energetic depictions of the monkey army clashing with demonic hosts build a visual crescendo toward the climactic confrontation and ultimate triumph of good over evil. Particularly evocative are the portrayals of Sita in captivity under the watch of ogresses, the restless monkey hosts scouring the earth for her, and Indrajit, son of Ravana, petitioning for celestial weapons to engage Rama’s forces. These are not merely episodes in the epic, but dramatic devices that heighten the anticipation of the inevitable resolution.

-

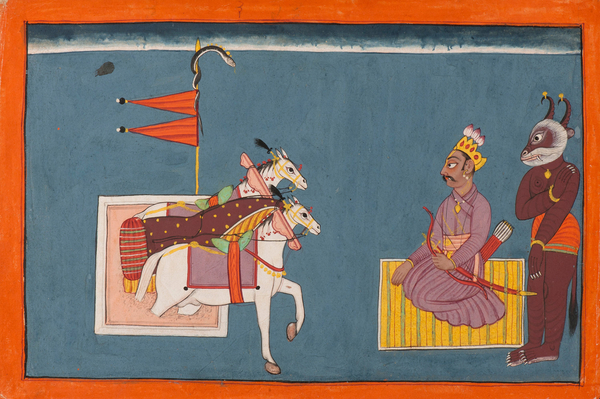

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710 -

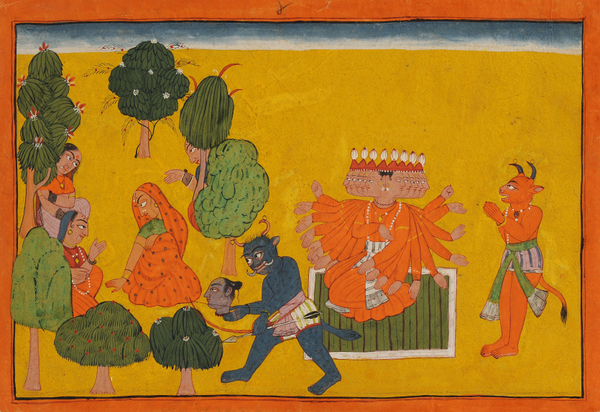

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710 -

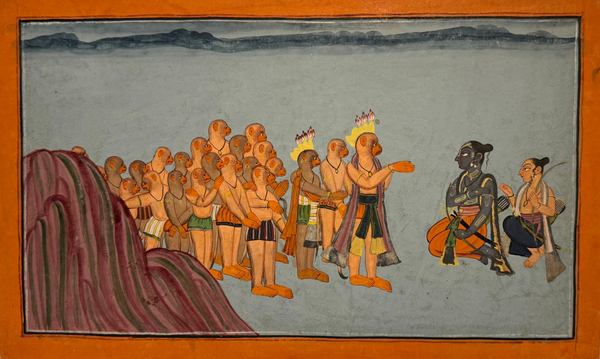

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710

-

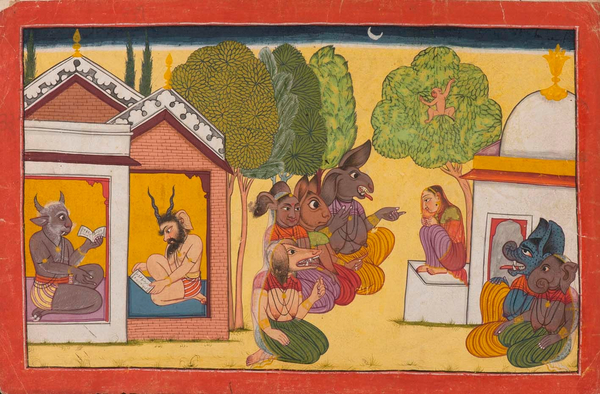

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710 -

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c 1700 -1710

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c 1700 -1710 -

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710

An illustration to the Shangri Ramayana, c. 1700-1710