The Master's Hand : Paintings and sumie by Nandalal Bose

From the late 1940's until his death in 1966, Nandalal Bose's work became increasingly personal and introspective. The technique that he selected for this last phase of his work is that of primarily monochromatic ink drawings otherwise known as sumi-e. He was first exposed to the sumi-e through exposure to artists and scholars visiting the Tagore family from Japan. Okakura Kakuzo came to India for a year between 1901 and 1902, and came back for the second time in 1912 when he gifted Nandalal a stick of ink from Japan. Rabindranath Tagore went to Japan in 1916 for the first time and later revisited the country in 1924 along with Nandalal. The artist’s own friendship with Arai Kampo from Japan further underscored his love for the sumi-e. The spirituality of his earlier works makes way to something which is subtly pervasive in these sumi-e paintings – intensely personal and inward looking.

Supratik Bose, Nandalal’s grandson once recalled ‘One morning – it must have been in the mid-1950s, when I was about 15 – I was in my grandfather’s studio grinding a stick of ink while he was printing a sumi-e. He was telling me how important the placement of the red seal was as it provided the only colour in the painting. I speculated where he might place it. He took great care preparing the seal, making sure it picked up enough vermilion seal ink to transfer to the paper. Then, with no hesitation whatsoever, his hand moved, and there it was – the seal was placed, not in a bottom corner, but near the middle of the painting. Surprised, I asked: ‘Why there?’ He said: ‘It wanted to go there – perhaps it is the sun rising.’ Indeed, the seal was just above the horizon, but I was left with a distinct feeling that there was no explanation for ‘Why there?’

Over his career Nandalal Bose used a variation of styles used by Chinese poet painters called hsieh-yi, and the Japanese pictorial idiom called hoboku. At this stage, however, his paintings move away from mythological subjects to more minimalist works expressed with a gestural immediacy. ‘Even the simplest strokes have a referent in nature, and they are made with the same motivation: seeking to find nature’s life rhythm. ... Such complexity and subtlety in Nandalal’s engagement with Pan-Asianism reveal the very traditionally Indian structure of his life, which began with apprenticeship, was followed by his years as a householder and professional in the public arena, and ended with what amounted to a renunciation of society and a turn toward a deep, inward looking spirituality.’ (Nandalal Bose, Vision and Creation, translated by K.G. Subramanyan, Kolkata, 1999, pp. 208-209)

In 1944, Nandalal Bose wrote the first of his three books on art theory titled Silpa-katha. In the book, he outlines his aesthetic theory that is essentially in tune with Indian spiritual traditions. Bose expresses that the realisation and expression of universal bliss (ananda) is the aim of art. He states, ‘the Universe has come out of Ananda. This delight includes and transcends all joys and sorrows. All artists work out of this creative delight; this decides whether any work is creative or not. The purpose of [true] art is to capture that rhythm of delight inherent in all creation, within their movement and measure. In this Art has some similarities with the spiritual quest (yoga). The spiritual quest drives towards the recognition of the essential unity at the centre of the diversity of creation, of the One by which you know all. Art too moves towards the vision of this great One. A Chinese artist has said, “In the eyes of a real artist the image of a blade of grass and that of god are equivalent; each can evoke the same aesthetic experience.” This should demonstrate how an artist gets at his “One”. No disrespect is meant here for the image of god; what is stressed is that the blade of grass deserves the same respect.’ (Nandalal Bose, Silpa-katha, Calcutta, 1944, unpaginated)

-

Nandalal BoseUntitled (Man in Storm)Signed in Bengali lower rightInk on card13.9 x 8.9 cm.1950s

Nandalal BoseUntitled (Man in Storm)Signed in Bengali lower rightInk on card13.9 x 8.9 cm.1950s -

Nandalal BoseUntitled (Tree)Signed with artist's seal centre leftInk on card13.8 x 8.8 cm.1950s

Nandalal BoseUntitled (Tree)Signed with artist's seal centre leftInk on card13.8 x 8.8 cm.1950s -

Nandalal BoseUntitled (The Pilgrims)Signed and dated in Bengali lower leftInk on paper23 x 17 cm.1954

Nandalal BoseUntitled (The Pilgrims)Signed and dated in Bengali lower leftInk on paper23 x 17 cm.1954

-

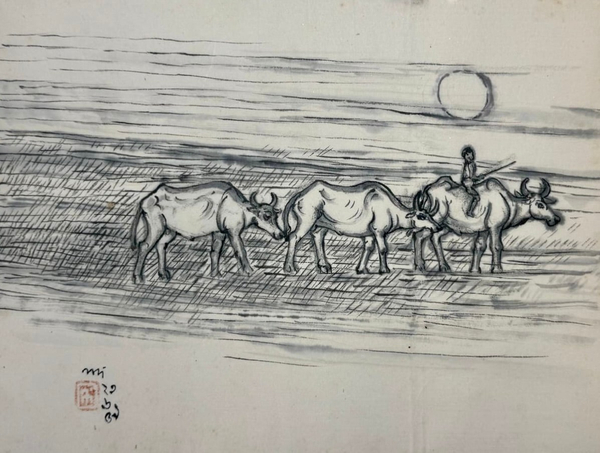

Nandalal BoseUntitledSigned and dated in Bengali lower leftInk on paper25 x 33.1 cm.1959

Nandalal BoseUntitledSigned and dated in Bengali lower leftInk on paper25 x 33.1 cm.1959 -

Nandalal BoseUntitledSigned and dated in Bengali lower rightInk and coloured wash on paper33 x 22 cm.1954

Nandalal BoseUntitledSigned and dated in Bengali lower rightInk and coloured wash on paper33 x 22 cm.1954 -

Nandalal BoseUntitled (The Pine Forest)Signed and dated in Bengali centre leftInk on paper laid on card21.1 x 17.1 cm.1954

Nandalal BoseUntitled (The Pine Forest)Signed and dated in Bengali centre leftInk on paper laid on card21.1 x 17.1 cm.1954